Traditional Ecological Knowledge

"If researchers wish to understand and address the impacts of climate change as well as rising inequality, Western science must recognize the value of and integrate TEK and the knowledge held by place-based Indigenous communities."[1]

Definition[edit | edit source]

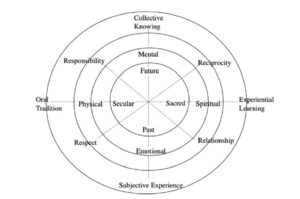

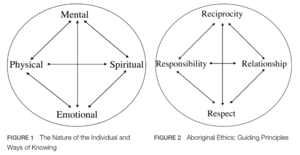

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.[2] TEK is but one of many ways of referring to this type of knowledge, also called indigenous knowledge, local knowledge, or traditional knowledge. This type of of knowledge is often holistic with a focus on relations, experiential, with varying expressions (stories, songs, dances, rituals, etc.), drawn from a local context and local understanding of "truth" and relationships. It is not simply about the knowledge gained in the past, but is dynamic and evolves with the past, present, and future.[3] "It is often about an ecologically and socially sustainable way of life, connected to every decision, and policies also (understanding how life is sustained by humans and the environment together)"[3]. When working with TEK, it is important to acknowledge the four R's: respect, relevance, responsibility, and reciprocity.

Indigenous Methodologies[edit | edit source]

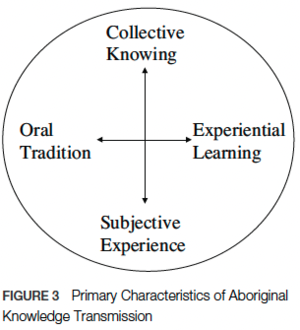

Aboriginal ontologies and epistemologies are rooted in worldviews that are inclusive of both the sacred and the secular. There exists the idea of "spiritual knowledge," and cannot be separated from TEK. The fundamental ontological principle is that the world exists in one reality composed of an inseparable weave of secular and sacred dimensions.[4] Within certain indigenous contexts, the concept of time is nonlinear, such that the past and the future co-exist with the present.[4] TEK is fundamentally about relationships between human beings, animals, plants, societies, the cosmos, the spirit world, and how to bring about balance and harmony between all things.[4] In the Western tradition, academics are considered “the experts” in their field of knowledge. In the context of [TEK], that is usually not the case, and therefore it is imperative that academics, especially those of us who are not Aboriginal, see ourselves as learners and act accordingly.[4]

Within Linguistics[edit | edit source]

Linguistics, the study of language, provides insight into a culture and its view of the natural world. Some indigenous peoples now have dictionaries for their languages. A native speaker can provide information about words, their meanings, associations and similarities. For example, the Yupik language on Nelson Island in Alaska is intrinsically tied to the environment –there are words to describe plants, activities, and elements in the Yupik language that are non-existent in other languages. These words help Yupik people to determine how they interact with their immediate environment.[5]

TEK can be utilised in a multitude of linguistic sub-disciplines, such as anthropological linguistics, sociolinguistics, and language preservation/revitalisation. By examining causes of language endangerment, it can help point out sustainability issues. For example, working with indigenous communities and their practices for cultural and environmental awareness. It fosters cross-cultural understanding, making sure academia have neutral societal, environmental, and ethical impacts.

Unfortunately, however, many indigenous peoples have lost their lands, languages, and/or cultures due to colonization. In order to preserve the languages, and ultimately, the cultures of indigenous populations, linguists may be asked to come help document the languages. In order to preserve TEK and the languages, there are revilatilzation and language preservation efforts happening the world over, but there is still a trend of languages dying out. Studies are revealing that the loss of TEK and linked practices increases community vulnerability to climatic and environmental change[1], so language and cultural preservation are imperative to a more sustainable future.

It must also be noted that in some cases, purely documenting a traditional story or song in a linguistic context removes the indigenous context, such that the song itself could be apart of a ceremony and hold deeper meaning, such that the words are not as important as the ceremony as a whole. Therefore, it is important as a linguist to be cognizant of linguistic/academic goals and the goals of the indigenous group being studied.

Connections between documenting traditional ecological knowledge and sustainability[edit | edit source]

TEK can be useful in a variety of other fields, and not just linguistics. Some examples are: anthropology, archaeology, biology, ecology, ethnography, environmental studies / conservation, geography, and sociology.

As described in Casi et. al., TEK with local indigenous peoples can be used for forest and water conservation with territorial mapping and working with local government for infrastructure and resource management[3]. Within the Sámi context, TEK is that has been passed down for generations has been used for sustainable reindeer herding, fishing, hunting and gathering.[3]

A prominent example of TEK being used for environmental sustainability are the yearly fires in California, in the United States, which have become worse over the years, and the local government is asking tribes to come in and do controlled burns to help decrease the impact of these fires[6]. This is a practice and ceremony that the tribes had done for hundreds, if not thousands of years, and have been unable to do until recently. This is a prime example of TEK of the land being beneficial to society and to the environment. In the U.S. state of New Jersey, controlled burns have been done with the help of the Lenape tribe for at least 100 years, and possibly before that as settlers eventually had to learn from the Lenape that without it, the native pine barrens would burn wildly.

Co-production of knowledge methods have offered better-situated and multidimensional understandings of complex sustainability issues, such as dynamic ecosystems, which are rapidly transforming due to climate change and global warming. TEK can offer different descriptions of events—for instance, a more practical view for the field of biosciences to produce their measurements and modelling. Local communities have been able to contribute to science, drawing from their practical experiences and views on environmental history, conservation practices, resource management, and knowledge of specific places.[3]

In the case of land conservation, documenting local knowledge (or TEK) can lead to a better understanding of biodiversity and methods of land preservation, especially when used alongside scientific knowledge. In some studies done on this subject, it was found that TEK and scientific knowledge, "were highly correlated and were instrumental in predicting perceptions of water-related ecosystem services, landscape change, increasing outdoors activities, and human-nature relationships."[7]

Relevant Wiki links:[edit | edit source]

Curated theme: Possible source of conflict between the SDGs and language maintenance

Curated theme: The relevance of addressing language endangerment for attaining the SDGs

Issues related to academic involvement in language revitalization

Language documentation and description

The natural ecology of language

Further Readings:[edit | edit source]

Battiste, Marie. Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education: A Literature Review with Recommendations. Ottawa: National Working Group on Education and Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2002.

Casi, C et al. 2021. Traditional Ecological Knowledge. In: Krieg C. & Toivanen R (eds.), Situating Sustainability. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33134/HUP-14-13

CBD Code of Conduct 2010. 2010. Convention on Biological Diversity Tkarihwaié:ri Code of Ethical Conduct to Ensure Respect for the Cultural and Intellectual Heritage of Indigenous and Local Communities Relevant to the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity. Nagoya, Japan: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 18–29 October 2010. Accessed 3 April 2020. https://www.cbd.int/traditional/code/ethicalconduct-brochure -en.pdf.

Cebrián-Piqueras, M.A., Filyushkina, A., Johnson, D.N. et al. Scientific and local ecological knowledge, shaping perceptions towards protected areas and related ecosystem services. Landscape Ecol 35, 2549–2567 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01107-4

Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301

Johnson, J.T., Howitt, R., Cajete, G. et al. Weaving Indigenous and sustainability sciences to diversify our methods. Sustain Sci 11, 1–11 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0349-x

McGregor, D. (2004). Coming Full Circle: Indigenous Knowledge, Environment, and Our Future. American Indian Quarterly, 28(3/4), 385–410. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4138924

Nelson, M., & Shilling, D. (Eds.). (2018). Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability (New Directions in Sustainability and Society). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108552998

Stori, F. T., Peres, C. M., Turra, A., & Pressey, R. L. (2019). Traditional ecological knowledge supports ecosystem-based management in disturbed coastal marine social-ecological systems. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00571

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://iee.psu.edu/news/blog/indigenous-knowledge-key-sustainable-future

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm#:~:text=Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20(TEK)%20is,environment%2C%20handed%20down%20through%20generations%2C

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Casi, C et al. 2021. Traditional Ecological Knowledge. In: Krieg C. & Toivanen R (eds.), Situating Sustainability. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33134/HUP-14-13

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/linguistics.htm

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/21/wildfire-prescribed-burns-california-native-americans

- ↑ Cebrián-Piqueras, M.A., Filyushkina, A., Johnson, D.N. et al. Scientific and local ecological knowledge, shaping perceptions towards protected areas and related ecosystem services. Landscape Ecol 35, 2549–2567 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01107-4