Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Difference between revisions

(added links to relevant pages) |

(definition, methodologies, images, links, readings) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:Curated Theme: Traditional Ecological Knowledge}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:Curated Theme: Traditional Ecological Knowledge}} | ||

incomplete | |||

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.<ref>https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm#:~:text=Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20(TEK)%20is,environment%2C%20handed%20down%20through%20generations%2C</ref> | ==== Definition ==== | ||

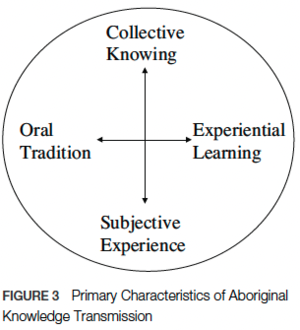

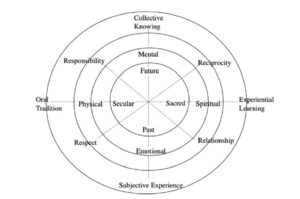

[[File:TEK.png|thumb|[[File:TEK big circle.png|thumb|Note: A Conceptual Framework of Aboriginal Knowing adapted from: Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. ''AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples'', ''9''(3), 189–203. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301</nowiki>]]Note: Primary Characteristics of Aboriginal Knowledge Transmission adapted from Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. ''AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples'', ''9''(3), 189–203. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301</nowiki>]] | |||

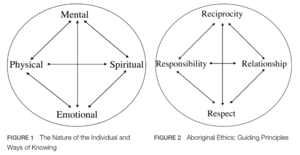

'''Traditional Ecological Knowledge''' ('''TEK''') is the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.<ref>https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm#:~:text=Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20(TEK)%20is,environment%2C%20handed%20down%20through%20generations%2C</ref> TEK is but one of many ways of referring to this type of knowledge, also called '''indigenous knowledge, local knowledge''', or '''traditional knowledge.''' This type of of knowledge is often holistic with a focus on relations, experiential, with varying expressions (stories, songs, dances, rituals, etc.), drawn from a local context and local understanding of "truth" and relationships. When working with TEK, it is important to acknowledge the four R's: respect, relevance, responsibility, and reciprocity. | |||

==== Indigenous Methodologies ==== | |||

Aboriginal ontologies and epistemologies are rooted in worldviews that are inclusive of both the sacred and the secular. There exists the idea of "spiritual knowledge," and cannot be separated from TEK. The fundamental ontological principle is that the world exists in one reality composed of an inseparable weave of secular and sacred dimensions.<ref name=":0">Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. ''AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples'', ''9''(3), 189–203. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301</nowiki></ref> Within certain indigenous contexts, the concept of time is nonlinear, such that the past and the future co-exist with the present.<ref name=":0" /> TEK is fundamentally about relationships between human beings, animals, plants, societies, the cosmos, the spirit world, and how to bring about balance and harmony between all things.<ref name=":0" /> In the Western tradition, academics are considered “the experts” in their field of knowledge. In the | |||

context of [TEK], that is usually not the case, and therefore it is imperative that academics, especially those of us who are not Aboriginal, see ourselves as learners and act accordingly.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

[[File:Aboriginal way of knowing diagram 2.png|thumb|Note: Two figures outlining TEK ways of knowing and ethical guidelines for engaging with TEK adapted from Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. ''AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples'', ''9''(3), 189–203. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301</nowiki>]] | |||

==== Within Linguistics ==== | ==== Within Linguistics ==== | ||

<blockquote>Linguistics, the study of language, provides insight into a culture and its view of the natural world. Some indigenous peoples now have dictionaries for their languages. A native speaker can provide information about words, their meanings, associations and similarities. For example, the Yupik language on Nelson Island in Alaska is intrinsically tied to the environment –there are words to describe plants, activities, and elements in the Yupik language that are non-existent in other languages. These words help Yupik people to determine how they interact with their immediate environment.<ref>https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/linguistics.htm</ref></blockquote>'''Connections between documenting traditional ecological knowledge and sustainability''' | <blockquote>Linguistics, the study of language, provides insight into a culture and its view of the natural world. Some indigenous peoples now have dictionaries for their languages. A native speaker can provide information about words, their meanings, associations and similarities. For example, the Yupik language on Nelson Island in Alaska is intrinsically tied to the environment –there are words to describe plants, activities, and elements in the Yupik language that are non-existent in other languages. These words help Yupik people to determine how they interact with their immediate environment.<ref>https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/linguistics.htm</ref></blockquote>TEK can be utilised in a multitude of linguistic sub-disciplines, such as anthropological linguistics, sociolinguistics, and language preservation/revitalisation. By examining causes of language endangerment, it can help point out sustainability issues. For example, working with indigenous communities and their practices for cultural and environmental awareness. It fosters cross-cultural understanding, making sure academia have neutral societal, environmental, and ethical impacts. | ||

==== '''Connections between documenting traditional ecological knowledge and sustainability''' ==== | |||

Anthropology | |||

Archaeology | |||

Biology | |||

Ethnography | |||

Environmental studies / conservation | |||

Sociology | |||

===== Relevance for SDG's ===== | |||

==== Links: ==== | |||

[[Language Endangerment]] | [[Language Endangerment]] | ||

| Line 22: | Line 40: | ||

[[Curated theme: Language, well-being, and the environment - sustainability from indigenous linguists' perspective]] | [[Curated theme: Language, well-being, and the environment - sustainability from indigenous linguists' perspective]] | ||

==== Further Readings: ==== | |||

Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. ''AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples'', ''9''(3), 189–203. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301</nowiki> | |||

Wilson, S. (2008). ''Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods''. Fernwood Publishing. | |||

References | References | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Traditional knowledge]] | [[Category:Traditional knowledge]] | ||

Revision as of 12:59, 24 January 2023

incomplete

Definition

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.[1] TEK is but one of many ways of referring to this type of knowledge, also called indigenous knowledge, local knowledge, or traditional knowledge. This type of of knowledge is often holistic with a focus on relations, experiential, with varying expressions (stories, songs, dances, rituals, etc.), drawn from a local context and local understanding of "truth" and relationships. When working with TEK, it is important to acknowledge the four R's: respect, relevance, responsibility, and reciprocity.

Indigenous Methodologies

Aboriginal ontologies and epistemologies are rooted in worldviews that are inclusive of both the sacred and the secular. There exists the idea of "spiritual knowledge," and cannot be separated from TEK. The fundamental ontological principle is that the world exists in one reality composed of an inseparable weave of secular and sacred dimensions.[2] Within certain indigenous contexts, the concept of time is nonlinear, such that the past and the future co-exist with the present.[2] TEK is fundamentally about relationships between human beings, animals, plants, societies, the cosmos, the spirit world, and how to bring about balance and harmony between all things.[2] In the Western tradition, academics are considered “the experts” in their field of knowledge. In the context of [TEK], that is usually not the case, and therefore it is imperative that academics, especially those of us who are not Aboriginal, see ourselves as learners and act accordingly.[2]

Within Linguistics

Linguistics, the study of language, provides insight into a culture and its view of the natural world. Some indigenous peoples now have dictionaries for their languages. A native speaker can provide information about words, their meanings, associations and similarities. For example, the Yupik language on Nelson Island in Alaska is intrinsically tied to the environment –there are words to describe plants, activities, and elements in the Yupik language that are non-existent in other languages. These words help Yupik people to determine how they interact with their immediate environment.[3]

TEK can be utilised in a multitude of linguistic sub-disciplines, such as anthropological linguistics, sociolinguistics, and language preservation/revitalisation. By examining causes of language endangerment, it can help point out sustainability issues. For example, working with indigenous communities and their practices for cultural and environmental awareness. It fosters cross-cultural understanding, making sure academia have neutral societal, environmental, and ethical impacts.

Connections between documenting traditional ecological knowledge and sustainability

Anthropology

Archaeology

Biology

Ethnography

Environmental studies / conservation

Sociology

Relevance for SDG's

Links:

Language documentation and description

Further Readings:

Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.

References

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm#:~:text=Traditional%20Ecological%20Knowledge%20(TEK)%20is,environment%2C%20handed%20down%20through%20generations%2C

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal Knowing in the Academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/linguistics.htm